But the promise of shelter, food, and medical care proves a temptation to many people, including Serge, whose freedom leaves him and Cassius both on the verge of homelessness. They wear uniforms and become, in effect, citizens apart, living as internees and indentured servants. The people who sign up for WorryFree are guaranteed lifetime room and board in barracks-like conditions, and receive lifetime employment, usually in factory jobs. And when Cassius begins to use his “white voice” (which is provided, on the soundtrack, by David Cross), he surges to success as a salesman-and discovers that his new responsibilities as a high-powered telemarketer to high-powered potential customers (an international list of businesspeople and politicians) involve selling the services of a controversial company called WorryFree, which is a sort of temp agency on an all-too-permanent basis. The well-dressed and well-paid members of that club take an elevator that’s reserved for them (regular employees take the stairs). The gold ring for which all of the telemarketers are striving is the status of Power Caller.

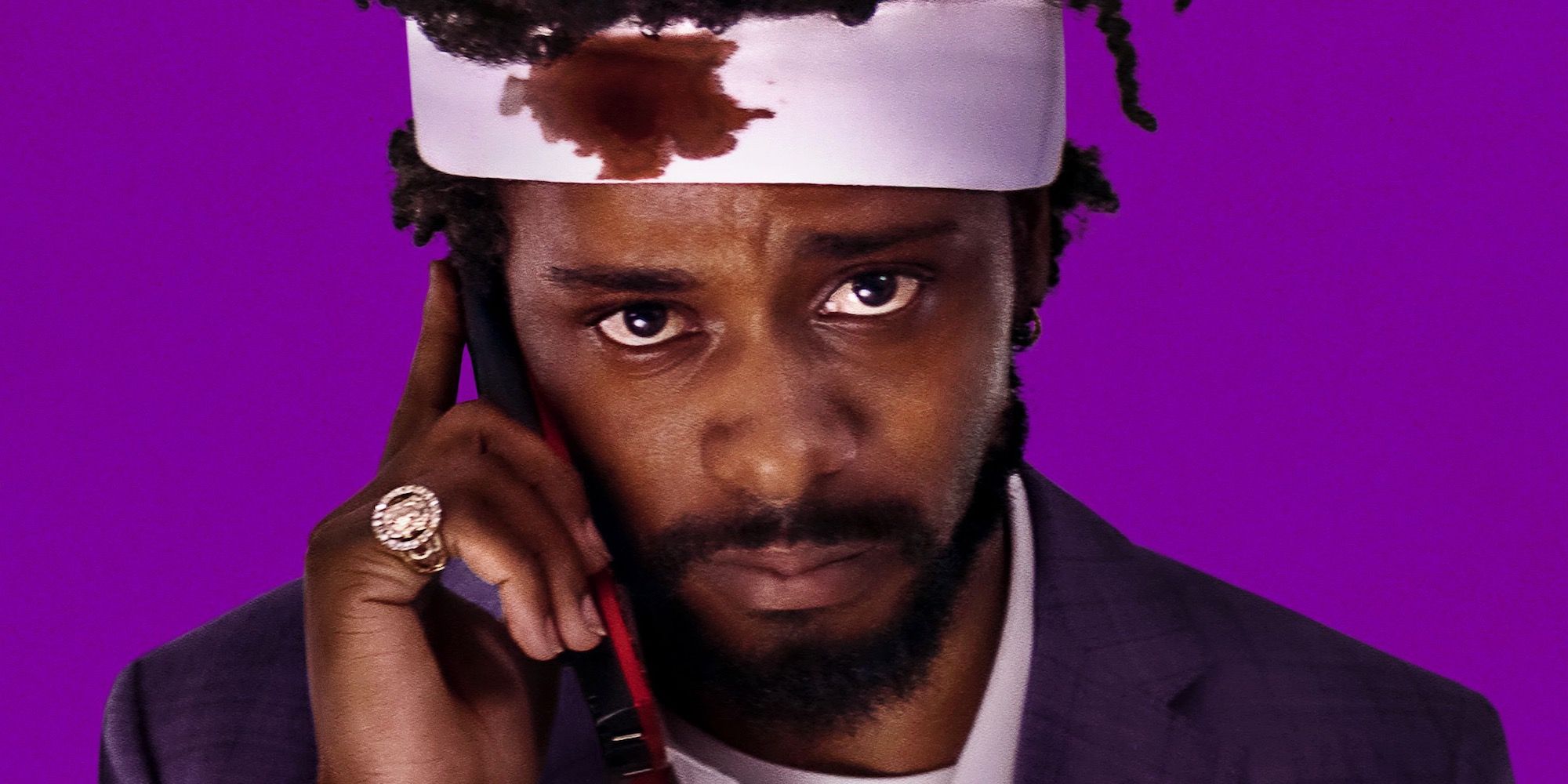

The “white voice,” he explains, is the one that Cassius would use “when you’re stopped by a cop,” a voice that would convey to buyers a sense that the seller has already got it made, and doesn’t need to make the sale-a voice that says “you’ve got your bills paid.” Langston’s voice has a steady oratorical power that conveys his deep, life-worn, cynical wisdom regarding more than sales it regards American life over all. Here, Riley’s writing is calmly, rhetorically majestic. His cubicle neighbor, Langston (Danny Glover), gives him some crucial advice: to use his “white voice” on the phone. Despite his dutiful efforts, he remains an underpaid failure. One of those tropes involves Cassius’s cold calls: he is, of course, bothering people at home, and, when they pick up the phone, he and his desk land with a crash in their kitchen, their bedroom, their bathroom, illustrating the wild inappropriateness of his intrusive spiel (he follows the company’s golden rule of “stuss,” or S.T.T.S., meaning Stick to the Script). Riley uses tropes from sketch comedy and cartoons in order to turn extreme and antic metaphors into an apt representation of the grotesqueries that have come to pass as ordinary. Our staff and contributors share their cultural enthusiasms. Another ping reveals that Cassius’s landlord, to whose house the garage is attached, is his uncle Serge (Terry Crews), who is pressuring his unemployed nephew for four months’ worth of unpaid rent, because he’s in danger of having his house go into foreclosure. Nonetheless, it qualifies him for the job on account of its sheer chutzpah.Ĭassius is in a relationship with an artist named Detroit (Tessa Thompson), and, shortly after he is hired, the scene shifts to the two of them together in bed in a tight space that is revealed, in a ping of cinematic imagination, to be a garage.

#Sorry to bother you full

At first, the comedy, cleverly constructed through sly directorial indirections, prevails: Cassius’s job interview, for instance, involves a deadpan, over-the-top display of his qualifications, which, we soon find out, is full of falsehoods.

#Sorry to bother you movie

The story-a futuristic one that’s nonetheless set in the present tense-is centered on the workplace, and focussed on the American dream of hard work, success, and prosperity, which the movie quickly depicts as a mockery, a delusion, and a nightmare. The title of the film alludes to the job that its protagonist, Cassius (Cash) Green (Lakeith Stanfield), a young man in Oakland, takes while in extreme need: he becomes a telemarketer in a shady company, called RegalView, that pays no salary, only commissions. The quantity, variety, and scope of its imaginative action yield a furiously panoramic view of ingrained political pathologies its wild humor channels a righteous rage into a vision of collective resistance. It’s a rapid, profuse, overwhelmingly inventive comedy of sorts that uses caustic satire to blast the veneer of normalcy off of societal horrors that typically go unchallenged-when they are even acknowledged. Yet many of the most scathing and insightful of recent political movies are fantasies, whether it’s “ Get Out” or “ Chi-Raq” or “ Arabian Nights,” “ Viktoria” or “ The Love Witch” or “ Black Panther” or “ Isle of Dogs.” Add another to that list: Boots Riley’s first feature, “Sorry to Bother You,” which opens this Friday. There’s a common assumption among critics that realistic films have an intrinsic claim on political importance.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)